Snowmaking at ski areas is a water-intensive activity that heavily relies on local rivers. (Photo courtesy CSU Libraries)

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Colorado River Compact, an innovative and influential legal agreement among seven U.S. states that governs water rights to the Colorado River. In recognition of this anniversary, the Colorado State University Libraries will be spotlighting a series of stories in SOURCE about the ripple effects of this 100-year-old document on diverse people, disciplines and industries in 2022.

Nestled in the spires of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains lie acres of crystalline snowpack, slowly carving the granite formations where they rest. The snowpack feeds a litany of creeks and rivulets that form the Colorado River, the bedrock of the West’s water supply.

Snow is crucial to fulfilling the Colorado River Compact’s promise of 15 million acre-feet allocations split between the upper and lower basins. Nearly 40 million people among seven Western states depend on the river’s swift currents to power their daily lives – which snowpack monitoring helps inform by creating more accurate predictions of how much snowmelt will make its way downstream.

Guided by the Compact’s allocations, snowmelt is a critical facet of water history and planning that is not often considered in detail, though it directly influences outdoor recreation and hydrology.

“It’s been 100 years since the Colorado River Compact has been signed, and one of the issues … is that the conditions in the river that existed prior to 1922 (were) not constant. and they were more than what we see in the long-term average. They had a short window and used those quantities to estimate who got what,” said CSU Professor Steven Fassnacht, who studies snow hydrology.

Hydrologists did not measure snowpack until 1936, when the aftermath of the Dust Bowl spurred the newly created Soil Conservation Service to measure snowpack.

These measurements helped give farmers a holistic perspective into the Colorado’s entire watershed and ensured they were aware of moisture levels before planting and irrigating crops.

However, snowpack measurements and actual water levels in the Colorado can vary significantly given the river’s dynamic nature, which has spurred hydrologists to take more complete snapshots of mountain ecosystems with improved snow measurements.

People may never be able to fully predict the river’s water levels, but modern snow measurement systems give scientists a better idea by measuring a wealth of environmental factors.

Today, a nationwide network of Snow Telemetry, or SNOTEL, sites inform the National Weather Service by giving daily information on precipitation, snowpack and soil moisture to better indicate how much snowmelt will end up in river sheds.

The Water Resources Archive

The CSU Libraries’ Water Resources Archive is a rich trove of primary sources that can advance research in many disciplines. Archivist Patty Rettig has compiled a list of the most relevant collections for those interested in snowpack and the Compact.

- Delph E. Carpenter and Family – Father of the Colorado River Compact and originator of the interstate river compact idea

- Ival V. Goslin – First executive director of the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority

- Royce J. Tipton – Civil engineer who designed some of the West’s largest water infrastructure projects and helped research the feasibility of creating Lake Mead

- Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr. – A foremost expert on Colorado Water Law who served as principal counsel to the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District and as a Colorado Supreme Court justice.

- Photographs of the Natural Resources Conservation Service – This photograph collection documents the efforts of the federal Snow Survey Program, which provides mountain snowpack data and water supply forecasts to Western states, dating from 1951 to 1996

- Irrigation Research Papers – This collection documents the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Irrigations Investigations Unit, originally established in Fort Collins in 1911. It includes the Colorado River Water Forecast Committee, which catalyzed snowpack measurement along the Colorado River with their snow measurements beginning in the 1940s.

Anyone interested in these collections can schedule an appointment to view them by contacting the Libraries’ Archives Reading Room at library_dl_specialcollections@mail.colostate.edu or by phone at (970) 491-1844.

Climate change impacts on snowpack

“Over the 80-to-90-year period of snow courses, these watersheds have changed,” Fassnacht said. “There’s been land use conversion, fire, insect infestation and a lot of disturbances to the forest. Climate change is making the conditions different – the system is getting warmer, and trees are growing at higher elevations.”

As the West’s climates become more varied and unpredictable, so too will the structure of snow, according to Fassnacht. Heavy snowfalls layered on top of melting snowbanks will create more variation between snow layers, which creates unstable snow. Greater variations in temperature between October and February further creates fluctuations in snowpack and weakens the stability of the bottom layer, which can trigger more avalanches.

Moreover, the Lower Basin downstream of Lake Powell, has experienced unprecedented drought in the past 20 years that has changed how California, Arizona, Nevada and New Mexico use water.

In fact, the Colorado River no longer reaches the Pacific, instead reduced to a scorched delta dotted with skeletal capillaries that whisper of the river’s once-powerful current. The Upper Basin upstream of Lake Powell, though, has not seen the same reduction in the overall amount of snowpack, although the distribution of snow has changed.

“We all want to be able to get the sound bite, tweet out the simple answer, but we’ve seen over the past few years that things are complex,” Fassnacht said. “In northern Colorado, stations at lower elevations are actually getting more snow, and higher elevations are getting less snow. That doesn’t match up with things warming up everywhere, because then lower elevations would have more rain than snow.”

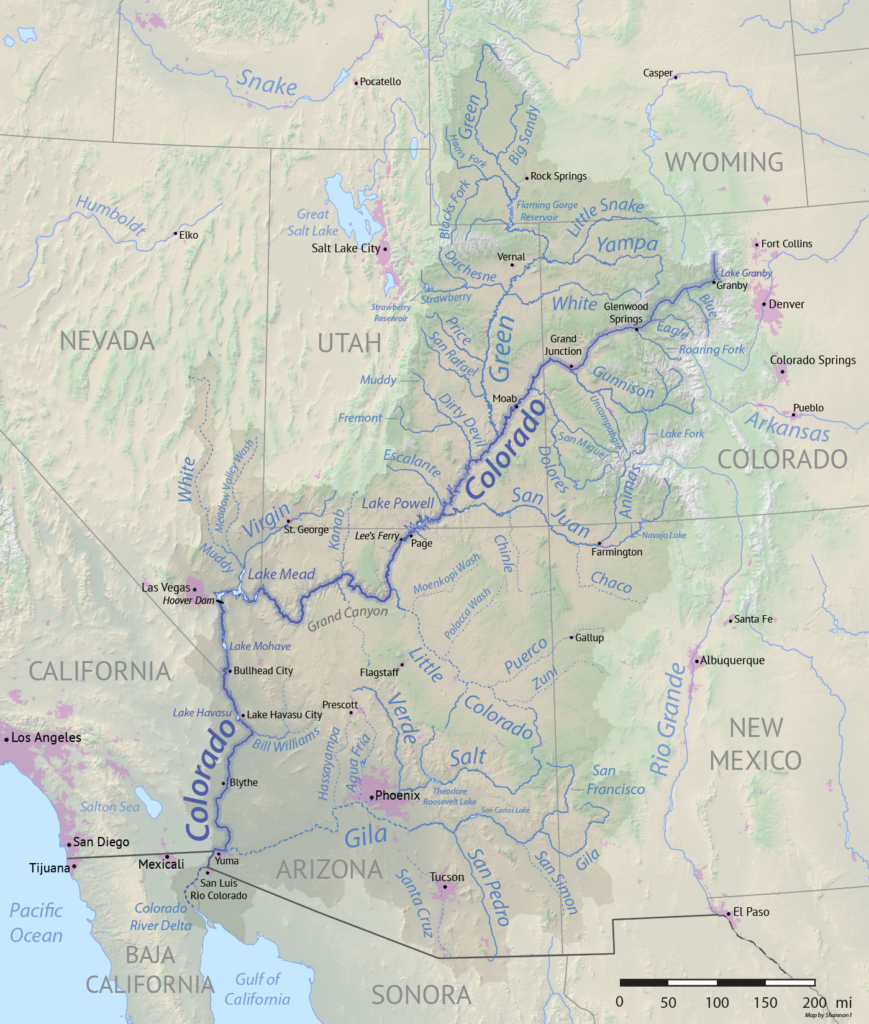

The Colorado River Basin extends from Wyoming to California and nearly 40 million people depend on the river. Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Snow and water usage at ski resorts

The federal Snow Survey Program provided mountain snowpack data and water supply forecasts to Western states. The U.S. Department of Agriculture produced a film in 1952 about the work of snow surveyors. (Photo courtesy CSU Libraries)

These findings hold particular relevance for snow-dependent activities like skiing and snowboarding. Keeping a slope covered in crystals requires massive quantities of water, which Fassnacht has helped watershed science students investigate in practicum courses at Copper and Winter Park.

Snowmaking is a water-intensive activity that heavily relies on local rivers, and as snowfall becomes more varied among elevations, it will become even more important for ski areas to reduce their water consumption – and even threatens the future of the Winter Olympics.

“The entire industry is reliant on frozen water falling from the sky every winter on a consistent basis, and it doesn’t, which makes skiing a difficult industry to make money. That is why ski resorts are more about real estate sales, retail and cheap season passes than just skiing,” said Michael Childers, an associate professor in history at CSU. “The real money has always been in real estate, which has led to the rampant growth of ski towns, which has led to increasing water use in those regions whose water is actually owned by agricultural and urban interests who are also increasingly thirsty.”

The future of an environmental good

Ultimately, the future of snow in the West depends on an improved understanding of the CRC and the Law of the River, the composite body of laws that govern the Colorado River’s water and infrastructure.

The Compact’s original designations to states – and the document’s reliance on uncharacteristically high-water levels – have allowed for the over-allocation of the river’s resources and its slow decline. With more inconsistent winters, the entire basin faces unprecedented water scarcity that could soon see the extinction of the high Rockies’ glimmering snowfields.

“Water is an environmental good – we’re only recently starting to recognize that with water law,” Fassnacht said. “Current water law restricts what we can do, but we need to consider the sustainability of what we’re doing with these water systems. We’re only starting to integrate the different players and stakeholders, but we need to work together more.”

He added: “We need to invite everyone to the table, have a frank conversation, and think about what the ramifications are, since this is a system that has global implications.”